There are moments in life that can redefine your retirement. Today, I want to share one of those moments with you.

It has to do with my mom and a broker at Smith Barney two decades ago.

My mom is a smart, independent person.

So, when she decided to invest her retirement funds with a brokerage firm called Smith Barney, she didn’t ask for my opinion.

Smith Barney was a prestigious institution. Its history went all the way back to 1873.

You may even remember its motto from a TV commercial in the 1980s, where actor John Houseman said: “They make money the old-fashioned way. They earn it.”

All that was before a telecom company called WorldCom went bankrupt on July 21, 2002. And not quietly, either.

I chronicled the rise and fall of WorldCom in my book Other People’s Money. It’s a twisted story.

This was the biggest corporate bankruptcy in U.S. history. WorldCom had assets of $107 billion at the time.

In its wake, WorldCom left a cesspool of $11 billion in accounting fraud.

Its former banks – including Citigroup, Bank of America, and JPMorgan – settled lawsuits with creditors for $6 billion.

And its CEO, Bernie Ebbers, served nearly 14 years in jail.

But before WorldCom went bankrupt, three things happened.

From Glowing Reports to Bankruptcy

First, WorldCom bought a lot of other firms after the Clinton administration passed the Telecommunications Act of 1996.

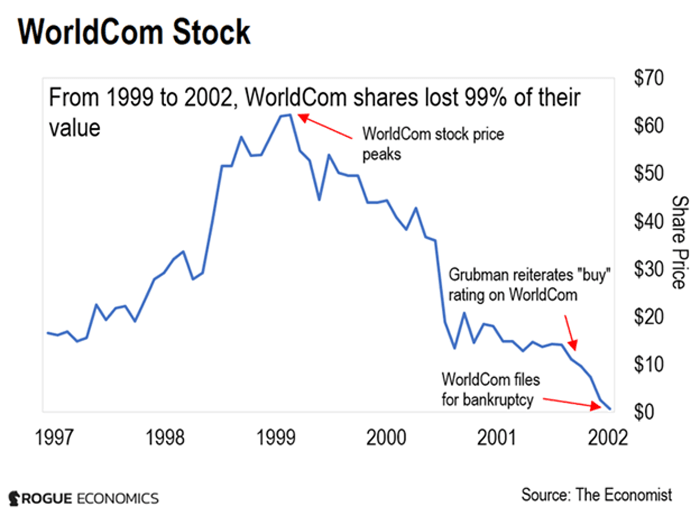

WorldCom’s stock rose from $16.50 to a peak of $62.30 in September 1999.

Second, a famous telecom analyst and managing director at Salomon Smith Barney wrote glowing research reports about WorldCom’s financial health.

This was even as its stock was bucking and it was announcing large accounting revisions. His name was Jack Grubman.

And third, WorldCom’s stock began plummeting into bankruptcy, as you can see in the chart below.

If you’re familiar with the book Liar’s Poker by Michael Lewis, you’ll know that Salomon Brothers was big in the 1980s.

But what you might not know is the incestuous relationship between Salomon, Smith Barney, and Citigroup.

Salomon Brothers merged with Smith Barney in 1997. Then, Travelers Insurance bought the combined company. And Citicorp merged with Travelers Insurance in 1998 to become Citigroup.

Yes, all that merging and name-changing can make your head spin. But here’s why I mention it…

Citigroup was involved in WorldCom at the investment banking level.

At the time, WorldCom was struggling to pay its debt. And as it turned out, it was also cooking its books to hide its true condition.

My Mom and WorldCom

While all that was happening, my mom’s broker was urging her to invest in WorldCom stock.

She followed his guidance… and invested nearly half of her retirement fund.

This happened during the months before WorldCom shares took a nosedive. She doesn’t remember the exact dates, but shares were already dropping steadily.

At the time, it might have seemed like a golden opportunity to “buy the dip.”

Because on the surface, WorldCom looked like a world-class company. And it’s not hard to imagine that her broker might have painted that picture for her.

But it turned out to be the worst financial mistake of her life.

And the “dip” in the case of WorldCom was not related to overall market behavior – but to fraud.

From its peak in 1999 to 2002, WorldCom shares plunged 99.1%. In the summer of 2002, the company filed for bankruptcy.

As a result, my mom lost nearly half of her retirement funds. And she wasn’t the only one who lost money.

Investors in WorldCom stock lost a total of $175 billion.

Don’t Make the Same Mistake

When my mom bought WorldCom stock, I was a managing director at Goldman Sachs.

But she didn’t tell me what happened until months after WorldCom’s bankruptcy.

By then, I’d walked away from Wall Street for good, disgusted by the greed and corruption there.

When I heard her story, I knew I’d made the right decision. I was furious about what happened to her.

First, because she lost that money by trusting a broker to act in her best interest.

Second, because of the incestuous relationship between Salomon Smith Barney and Citigroup.

It was such that certain brokers could convince their customers to purchase stock in companies that were heading south.

Just like my mom’s broker urged her to buy WorldCom.

They could tout internal positive research as a way to encourage retail customers to buy that stock.

Remember Jack Grubman, managing director at Salomon Smith Barney?

He maintained a “buy” recommendation on WorldCom even as it dove from its peak of over $60 a share in 1999 to $7 a share in 2002.

On February 8, 2002, he even reiterated his “buy” rating, according to Salomon Smith Barney research reports.

That was one major reason my mom’s broker used to convince her to buy WorldCom stock. A few months later, WorldCom declared bankruptcy.

Today, the historic Smith Barney name is no more.

In 2009, Citigroup sold part of its Smith Barney retail brokerage business to investment bank Morgan Stanley.

That combined company – or “joint venture” in Wall Street speak – was called Morgan Stanley Smith Barney Wealth Management.

But, in 2012, Morgan Stanley dropped the Smith Barney name. It simply had too much baggage.

What This Means for You and Your Money

What my mom learned from her experience with Smith Barney is that you have to be wary of brokers.

Especially ones that have an institutional relationship with the company they’re recommending.

So, here’s my advice on your brokerage accounts, especially for your retirement funds:

1. Be wary of brokers – even the big ones.

It’s best to keep your retirement funds with companies that aren’t owned by any mega-banks.

That’s a good way to know that the recommendations they offer you aren’t tied to positions those banks might have or might publicly endorse.

Independent brokerages include Ameriprise Financial and Osaic (formerly Advisor Group).

2. Don’t put all your investment eggs in one basket – and don’t invest it all at one time.

Spread your risk, even when you’re investing in what seems like an amazing opportunity.

Don’t invest all your capital in a single name or idea. And invest in small increments, rather than all at one time.

For example, say you’ve set aside $1,000 to invest in a company you like.

You might choose to invest $500 now and the other $500 in a few months or when you see a dip.

You can also consider investing smaller amounts over a longer period of time. This is what we call “legging in,” or “dollar-cost averaging.”

None of us can time the market with 100% accuracy. And none of us can get every investment right.

This sort of approach can help you protect your nest egg if one of your investments doesn’t work out.

Happy investing,

|

Nomi Prins

Editor, Inside Wall Street with Nomi Prins