They say two things are certain – death and taxes.

Well, here’s a third: The debt ceiling will always rise. That’s no matter how much arguing and posturing goes on at Capitol Hill.

Think of it like having no limit on your credit card. Ever.

Yet, the Congressional tiff about the debt cap is why Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen went ballistic last week.

In a letter to new House Speaker Kevin McCarthy, Yellen painted a grim picture of what will happen if Congress doesn’t raise the debt ceiling.

She said that, after tomorrow, the Treasury Department would have to start taking “extraordinary measures” to avoid defaulting on its debt.

“Failure to meet the government’s obligations would cause irreparable harm to the U.S. economy,” she wrote.

But in today’s essay, we’ll dial down Yellen’s angst. And I’ll give you a one-click way to turn Congress’ squabble into potential profits.

Congress’ Annual Circus

The debt ceiling quagmire in Congress is an annual circus.

Politicians use the threat of not voting to raise it as a horse-trading technique. In other words, to gain an advantage in discussions about the budget and spending.

The irony? Congress actually deals with spending under an entirely separate budget process.

The upshot? Congress always raises the ceiling eventually.

Now, for those who don’t know, the debt ceiling is the limit on the amount of federal debt that can be outstanding at any time.

Congress created it in 1917 through the Second Liberty Bond Act. That was four years after the Federal Reserve System was created.

It was also the year the U.S. entered World War I.

The war required a lot of borrowing. But it took too long to vote on every single issuance of new bonds (or debt).

Under the Second Liberty Bond Act, the Treasury could borrow money, in the form of bonds. Separately, by that time, the Fed had the power to purchase bonds.

In theory, the Treasury could only borrow up to a cap set by Congress. Once it went past the cap, Congress would need to pass new legislation to raise the limit.

Hence the current situation.

A Bipartisan Farce Since 1917

Raising the debt ceiling has been one of the most consistently bipartisan policies of Congress. It’s an endlessly upward-moving target.

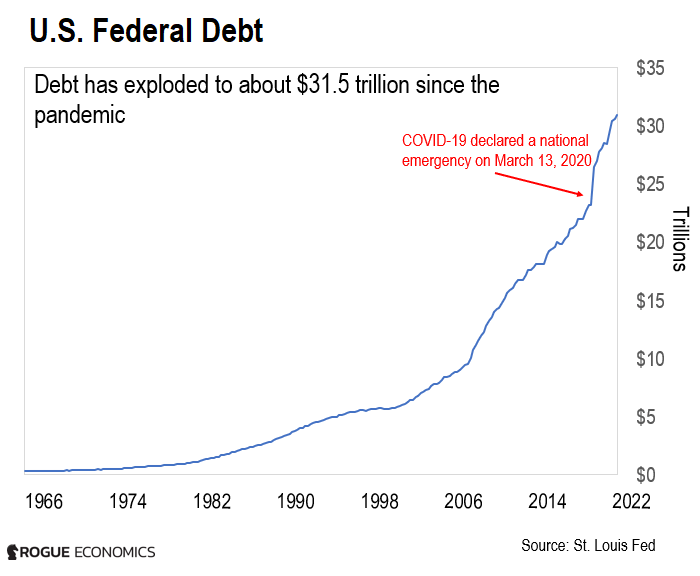

Since 1917, Congress has voted to raise it more than 100 times. The last time was in December 2021, when they raised the ceiling by $2.5 trillion. Now it stands at $31.4 trillion.

So it’s not surprising that U.S. national debt has increased under every president since Herbert Hoover.

That’s the catch. The debt ceiling doesn’t keep a lid on debt.

If it did, we wouldn’t find ourselves in this period of Great Distortion. The last 15 years are a case in point…

During the financial crisis of 2008, the size of U.S. debt outstanding rose to $9.65 trillion. The pandemic pushed that to $23.53 trillion.

And since the pandemic, it exploded by another nearly 50%, to about $31.5 trillion. (That happens to be a bit over the debt cap of $31.4 trillion anyway.)

Technically, if the U.S. government hits its debt ceiling, it can’t issue new bonds. That means it would run out of money to pay its debt obligations.

No doubt, a default would hurt the U.S. economy and international markets. Plus, it’d be embarrassing for the U.S.

That’s where the Treasury Department would come in with “extraordinary measures,” as Yellen called them. But here’s what Yellen has wrong…

Default is the failure to pay interest, or principal, on U.S. Treasurys. It’s not the failure to pay on any old government obligation.

And the U.S. has never defaulted on its debt.

That’s why all the fearmongering by both parties about the possibility of a U.S. default is so farfetched.

Yes, a U.S. debt default would be bad. But it’s not likely. That’s because the debt ceiling only sets a limit on increased borrowing.

That means if a Treasury bond became due, the Treasury Department could issue debt to replace it and remain under the ceiling.

Or the government could use tax revenues to pay its debt, without issuing new debt, since legally the U.S. must pay its debt before anything else.

What This Means for Your Money

The good news is, none of this debt ceiling drama affects acts that the government has already passed and funded.

And a big one on my radar is last year’s Inflation Reduction Act (IRA). That act is 100% certain to give specific domestic sectors a major boost.

In fact, one of my close contacts told me he’s seeing a lot of new manufacturing projects in the Midwest.

“They are all centered on provisions set out in the IRA passed back in August,” he said. “Some very interesting dynamics going on here.”

Some of the domestic sectors I’m watching are:

-

Rare earths production,

-

Industrial metals production and mining,

-

And investments in battery technology, infrastructure, and energy.

To take advantage of this, consider buying the SPDR S&P Metals & Mining ETF (XME).

It’s an exchange-traded fund focused on U.S. metals and mining stocks. And it holds industry heavy-hitters like Cleveland-Cliffs (CLF) and Freeport-McMoRan (FCX).

Regards,

|

Nomi Prins

Editor, Inside Wall Street with Nomi Prins

P.S. Over the past 20 years since I quit Wall Street, I’ve spent countless hours working with our federal officials. And where government money goes, the markets follow. So it pays to look closely at the legislation coming out of Washington.

Now, thanks to a law that just went into effect this month, I believe the government has already picked the biggest winners and losers for 2023. And at a special event last week, I pulled back the curtain on a little-known strategy that can give you a chance to profit from both – at the same time.

Plus, I gave away the name of one stock to buy… and one to avoid… for free. If you missed it, I asked my publisher to keep it online for a little while longer. Watch the replay right here.