Welcome to our Friday mailbag edition!

Every week, we receive some great questions from your fellow readers on our recently published essays. And every Friday, I answer as many as I can.

Before I get to your questions today, I want to quickly tell you about an emergency briefing I’m holding next Wednesday, September 28 at 8 p.m. ET.

See, 20 years ago, my mom lost nearly half of her nest egg in a historic distortion. Her big mistake was trusting her broker… and the Wall Street spin machine.

And now, a new distortion in the energy market could result in a similar fate for unprepared Americans.

I want to make sure you’re not one of them…

See, folks who take action and prepare right now could potentially make up to 10x their money with a few key moves.

That’s why I’m combining everything I learned in my 15 years on Wall Street to help ordinary Americans make extraordinary gains when big moves happen in the energy market.

I hope you’ll join me at the event on September 28. I’ll explain what’s coming in the energy crisis and how you can prepare your portfolio. Just go here to sign up for free.

Now, let’s get to today’s mailbag, starting with these pertinent questions from readers Kristine F. and Alan G. about the energy transition…

I have wireless charging devices. I get it.

Thing is, most of the electricity in those power lines you are counting on comes from coal or petroleum. Where is the energy supposed to come from?

Wind farms and solar panels just don’t cut it. And most places I read about are not ready to go nuclear. So, what’s your power source?

– Kristine F.

Seems to me that pushing renewable energies too hard too fast, while shrinking fossil fuels too hard too fast, could send this country into a dangerous lockdown, a depression, hyperinflation, or a frozen economy. It could also cause frozen transportation or – much worse – riots in the streets.

I’m not hearing wise, cautious voices as to how to coordinate this well in timely ways soon enough to save us from disaster. Do you know otherwise?

– Alan G.

Thanks Kristine and Alan for writing in. I really do appreciate it. Those are excellent observations and questions.

I want to be very clear here. There are two things going on in the world right now.

We have a critical need for fossil fuel-based energy sources. And we also have a transition to build and develop efficient technologies for utilizing more renewable and sustainable energy sources.

And you’re right, we don’t have enough of the latter to cover the world’s energy needs right now.

We also have a lot of factors causing distortion in the supply of energy based on oil, natural gas, coal, and even firewood.

So there’s no overnight process here. And it is dangerous to assume there is, or that we can abandon fossil fuels too quickly.

We can’t just stop using fossil fuels. That’s just not practical.

Nor is it realistic. We can’t just flip a switch to use other forms of energy for all our power needs.

So we are in a very unique period of history, where both are happening at the same time.

And far from being a miracle overnight cure for all our energy woes, I believe the energy transition will take a long time to play out. But it will happen.

Now, while some investors are going full steam ahead, I prefer a more measured approach to investing in the transition.

Just like not all technology companies turned out to be Google, not every company developing a new technology to support the energy transition will succeed. And not every company that secures government funding or private investment will deliver on its promised gains.

So those who invest blindly in the green energy space risk getting hurt.

That’s why in my investment advisories, I always deeply analyze each company I recommend. I include the potential risks involved and things to look for as the company grows.

And my team and I keep a close eye on all of our recommended companies and provide regular updates.

And as I mentioned above, I’ve developed a strategy that is unique to this moment. At my emergency briefing next Wednesday, September 28 at 8 p.m. ET, I’ll tell you all about it.

So reserve your spot here… and then read on below for more great questions from your fellow readers on my recent essays.

Next, reader Carole E. has a great question related to my recent essays on the revival of the nuclear energy industry (catch up here and here). She’s concerned about nuclear waste…

I’m really enjoying your Inside Wall Street mailings and the debate about energy.

My question is: Can nuclear really be considered safe, given that we are yet to come up with an environmentally friendly means of dealing with nuclear waste?

Are we not leaving a toxic legacy for future generations in the hope that someone might find an answer in the meantime?

– Carole E.

Hi Carole. Thanks for writing in. There’s no question that nuclear waste is hazardous because of its radioactive properties. If not properly managed, it could be a risk to the environment and human health.

I say “could” because since the advent of the civil nuclear power industry, properly managed nuclear waste has never caused anyone harm.

I also think it’s important to consider a few key questions that often go unaddressed in the nuclear waste debate.

Specifically, “How much waste does nuclear create?” and “How long before it’s no longer dangerous?”

First of all, nuclear fuel is very energy dense. This means you don’t need a whole lot of it to produce huge quantities of power. Especially when compared to other energy sources like coal and gas.

It also means that a relatively small amount of waste is created in the process.

For example, a typical nuclear power station produces 1 gigawatt (GW) of power per year, on average. That’s enough to meet the electricity needs of more than a million people.

But it produces only three cubic meters of high-level waste per year. And it produces no direct carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions.

This waste is kept in wet storage facilities known as spent fuel pools for up to 20 years. After that, it goes into large concrete-steel silos, or dry casks, awaiting permanent disposal in an underground geological repository.

For perspective, a coal-powered plant that generates 1 GW of power produces roughly 300,000 cubic meters of toxic ash waste each year. And more than 6 million tons of CO2.

Most power plants dispose of the ash waste in surface impoundments or in landfills. Others (especially in developing countries) may discharge it into a nearby waterway under the plant’s water discharge permit.

Note that “high-level” nuclear waste just means it’s highly contaminated, mostly coming from used (or spent) nuclear fuel. And it’s important to underscore that this type of nuclear waste makes up only 3% of the total waste volume.

In fact, in France, where fuel is reprocessed, just 0.2% of all radioactive waste by volume is classified as high-level. Keep in mind that France generates a larger percentage of its electricity from nuclear power than any other country worldwide.

Lightly contaminated items (with only 1% of the total radioactivity), such as tools and work clothing, make up the vast majority of the nuclear waste (about 90%). They are routinely discarded in near-surface disposal facilities due to their low (and short-lasting) radioactivity.

Now, none of this is to say that coming up with appropriate disposal solutions for nuclear waste shouldn’t be at the top of the industry’s list of priorities.

But while it’s still very much a work in progress, things are starting to fall into place.

Case in point: nuclear fuel recycling.

Yes, you read that right. Most of the material in used nuclear fuel can be recycled.

And while some nations (most notably the U.S.) continue to treat used nuclear fuel as waste, many others have started recycling it to generate more power. These include France, Russia, and Japan.

Advanced reactor designs have already been developed that can consume or run on used nuclear fuel. The trick is getting this to a commercial scale to ensure that it is done economically.

If these efforts prove successful, it would be a game-changer for the industry.

There are also interesting things happening in Finland, where a first-of-its-kind deep geological disposal site is due to enter operation in 2025.

The international consensus is that geological disposal deep underground is the safest way to dispose of high-level nuclear waste.

The pioneering facility, called Onkalo – which means “cavity” or “pit” in Finnish – is being built 400 to 430 meters down into the bedrock. It’s estimated to cost about $3.5 billion. Trial runs will begin in 2023.

Other countries, too, have already developed plans for similar sites, including France, Sweden, Japan, and the U.S. They’re watching the progress at Onkalo closely as they advance in their own efforts towards geological disposal.

I hope that helps.

Now, switching gears, reader Brendan V. is concerned we’re headed for hyperinflation…

Money velocity is off a cliff. How can anyone think “peak inflation,” when money isn’t even moving through the economy?

What happens when people start dumping cash for goods and services? Hyperinflation starts off slow and finishes in a flash.

– Brendan V.

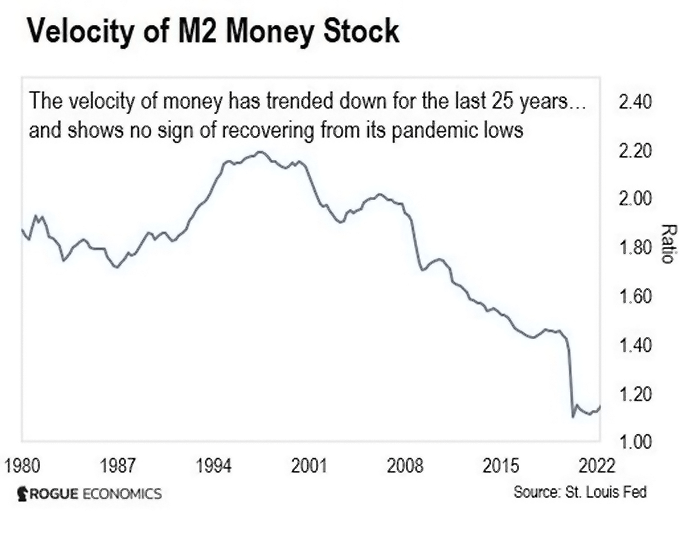

Hi Brendan, thanks for that important observation and your questions. Indeed, the velocity of money has been in free-fall since the early 2000s.

The velocity of money measures the rate at which money changes hands throughout an economy or moves from one point to another.

The lower the velocity of money, the less dynamically money is flowing through an economy, which is not a healthy sign.

In a healthy, vibrant economy, you’d expect money to change hands and across goods and services more actively.

But the velocity of the U.S. dollar has nearly halved over the last two and a half decades. You can see that in this chart from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis…

And as you can see in the chart, the velocity of money fell off a cliff during the pandemic… and hasn’t recovered all that much since then.

That said, peak inflation – or high inflation, as we are currently dealing with – is an indication that there’s not enough supply relative to the demand for actual items or services.

The two don’t have to be related.

For instance, we can have an energy squeeze that pushes fuel prices upward, and still have a low velocity of money. That’s what we’re seeing now.

We can also have a situation where people don’t have enough money to pay for necessary things – like energy, food, and housing – and are therefore unable to pay for other things.

That would reduce the money velocity even more. But it might not reduce the cost of items that are contingent on supply and demand – like energy.

And yes, that can spell a looming, bad hyperinflation scenario.

Officially, hyperinflation is when the rate of inflation goes above 50% per month.

Now, while inflation has risen rapidly here this year, and may continue to do so in the coming months, I’m not sure we’ll get to that point. I certainly hope not.

I think lower growth in the interim might have a dampening effect on demand and prices, and thus inflation.

GDP growth has gone negative this year. In the first quarter, GDP fell by 1.6%. It dipped by a further 0.6% in the second quarter.

So technically, we’ve entered a recession. A recession is defined as two consecutive quarters of negative GDP growth. But whether this will result in lower inflation remains to be seen.

The third-quarter GDP growth estimate is due next week. And the September consumer price index (CPI) data will be released mid-October. So keep an eye out for those.

That’s it for this week’s mailbag. Thanks again to everyone who wrote in.

Before I go… just a reminder about my event next Wednesday, September 28.

For anyone who tunes in, I’m even giving away the name of one of my favorite stocks, which I think could become a blue chip over time.

Just go here to sign up, and I’ll see you there!

In the meantime, happy investing… and have a fantastic weekend!

Regards,

|

Nomi Prins

Editor, Inside Wall Street with Nomi Prins

P.S. If I didn’t get to your question this week, look out for my response in a future Friday mailbag edition. And if there are any other topics you’d like me to write about, I’d love to hear from you. You can write me at [email protected].

I do my best to respond to as many of your questions and comments as I can. Just remember, I can’t give personal investment advice.